The ISSE is the Irish Survey of Student Engagement. According to studentsurvey.ie the purpose of the survey is to:

“provide benefits to each institution and its students by helping to improve feedback and appropriate follow up action. Objectives identified for the taught survey include:

- To increase transparency in relation to the student experience in higher education institutions

- To enable direct student input on levels of engagement and satisfaction with their higher education institution

- To identify good practice that enhances the student experience

- To assist institutions to identify issues and challenges affecting the student experience

- To serve as a guide for continual enhancement of institutions’ teaching and learning and student engagement

- To document the experiences of the student population, thus enabling year on year comparisons of key performance indicators

- To provide insight into student opinion on important issues of higher education policy and practice

- To facilitate comparison with other higher education systems internationally

All of this fine. But when you get down to the actual questions things get a little odd. Bear with me as I go through each question, one by one.

Questions related to higher-order learning

The first and most obvious point to be made here is that what constitutes “higher-order learning” is by no means clear. These days I suspect that many in the world of education associate higher-order learning with things like inquiry based learning, problem-solving, group work etc. because that’s the constructivist philosophy. On the other hand, many would believe (me included) that there is no hierarchy of learning but there is a progression from acquiring new knowledge (by being taught) to developing an understanding of that knowledge (where understanding is really just more knowledge) to being well practiced at using that knowledge. But anyway, let’s look at the questions.

During the current academic year, how much has your course work emphasised…

1.Applying facts, theories, or methods to practical problems or new situations

Now I’m sure an engineering student would reply “very often” but what about someone studying English literature or French or philosophy? There is an obvious bias in this question towards an instrumentalist view of education.

2. Analysing an idea, experience, or line of reasoning in depth by examining its parts

This seems like a reasonable but not very enlightening question because one would have thought that examining anything in depth by examining its parts was a given in higher education.

3. Evaluating a point of view, decision, or information source

This question seems to be aimed at students in the humanities apart, perhaps, for the “information” bit. Most students studying on STEM programmes spend most of their time learning the fundamentals of their discipline. “Points of view” don’t arise very often except perhaps in final year where students might be asked to evaluate an academic paper.

4.Forming an understanding or new idea from various bits of information

This just seems a bit wishy-washy and I think the average student is likely to go for a middle ground here. Indeed if you look at the breakdown of the responses to the 4 questions in this section (each column represents from “very little” to “very much”) nothing startling or even interesting emerges.

Questions relating to reflective and integrative learning

Again you could argue about what exactly these words mean but let’s plough on anyway.

During the current academic year, how often have you…

1.Combined ideas from different subjects/modules when completing assignments

The implication here is that integrating ideas from modules is a good in itself – and it is. I have to say that in my experience it’s a rare thing for students to integrate their learning, which is why I’m surprised that the data show that 39.2% of students combined ideas from different subjects “often”.

2.Connected your learning to problems or issues in society…

I’m not sure why this question is being asked. There’s an ideology at work here and it’s the belief that education should be immediately relevant or, to use a buzz word of progressive education, “authentic”. But think of a person studying pure mathematics or English literature, or music or even physics. Is it not enough to simply study those disciplines without having to divert into discussing the topical issues of the day?

3.Included diverse perspectives (political, religious, racial/ethnic, gender) in discussions or assignments

Now we’re getting into dangerous territory. There is a growing tendency for almost every activity or body of knowledge to be seen through a the lens of internationalist. It’s a tendency that has had a crushing effect on many American Universities and it is beginning to infiltrate British and Irish ones. Sure, talk about these issues in sociology or history but let’s keep the thought police away from other disciplines.

4.Examined the strengths and weaknesses of your own views on a topic or issue

Again, this is a question that will be fine for some disciplines but puzzling to others and if a question has meaning for some disciplines but not for others then should it really be in the survey?

5.Tried to better understand someone else’s view by imagining how an issue looks from their perspective

I’m now thinking what a chemistry student would make of this question. Of course, students will, from time to time, question each other about how to solve a problem in organic chemistry or how to conduct an experiment but I don’t think that’s what the question is really asking.

6.Learned something that changed the way you understand an issue or concept

I would have thought that most students would answer “often” or very “often” to this because surely changing how you understand things is the very purpose of higher education.

7.Connected ideas from your subjects/modules to your prior experience and knowledge

Hopefully a majority of students would reply often or very often to this question.

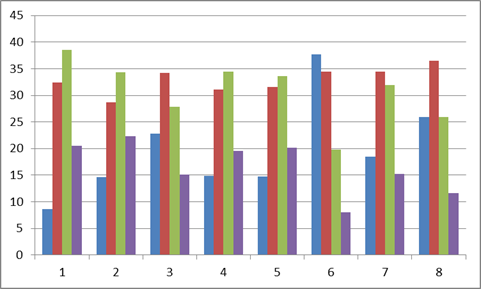

Looking at the replies to these questions, we find a bit more variability than before. The biggest outlier relates to the question on diversity (third set of columns) where there is a high “never” score. That’s good.

Questions relating to quantitative reasoning

In my view these questions are pointless since the answer is so discipline-specific.

During the current academic year how often do you

1.Reached conclusions based on your analysis of information (numbers, graphs, statistics etc)

This is a reasonable question but the breakdown of the question replies will be little more than a breakdown of the disciplines within the survey sample.

2.Used numerical information to examine a real-world problem or issue (unemployment, climate change, public health etc.)

Again we see this term “real-world” crop up. What does it mean? If a chemical engineering student uses numerical information to evaluate the performance of reactor, is a reactor the “real world”. It’s interesting that the question gives examples of ‘topical’ issues which perhaps shows the mindset of the questioners.

3.Evaluated what others have concluded from numerical information

There’s nothing wrong with this question but I’m not sure what it adds to the previous one other than to hint at the idea of peer evaluation.

The breakdown of replies reveals a high proportion of “nevers” which makes sense consider the focus of the questions

Question Relating to Learning Strategies

During the current academic year how often have you

1.Identified key information from recommended reading materials

2.Reviewed notes after class

3.Summarised what you learned in class or from course materials

All of these questions are mildly interesting.

The key thing, though, about this section is that it is a massive lost opportunity. There is huge scope here to really dig deep and find out how and when students study. My guess is that most students don’t study effectively even if they don’t cram – many spend their time reading and re-reading notes and/or highlighting. These are notoriously poor strategies. Furthermore, previous student surveys, when they asked the question “how often do you study”, found that student study levels are nowhere near the levels they need to be at. Oddly enough, that question has been removed from the survey.

I won’t give the breakdown of replies to these questions other than to say that only 15.3% of students study their notes “very often” after class while 41.6% “sometimes” study their notes. It’s a pity students weren’t asked when they study their notes because there is an optimum time for revisiting your notes – neither too soon nor too late.

Questions Relating to Collaborative Learning

Collaborative learning is fetish of progressive educators because they believe that learning is a social process, not a solitary one. They also see education in instrumentalist terms and deduce that since collaboration is often required in the workplace, then it makes sense for students to learn collaboratively (which is a bit like saying rugby players should train by playing full-contact 15-a-side matches). The very fact that the following questions are being asked is because the underlying philosophy of the ISSE is a constructivist one.

During the current academic year how often have you

1.Asked another student to help you understand course materials

2.Explained course material to one or more students

3.Prepared for exams by discussing or working through course material with other students

Taking these three questions together, what is really being asked is what the class ‘vibe’ is. Students who know each other and get on well together tend to collaborate – I see it all the time in my laboratory modules when individuals are struggling with calculations. As for studying together for exams, I’d be neutral on this one – it all depends on your personality.

4.Worked with other students on projects or assignments

The replies to this question are mildly interesting but not fascinating. Only 10% of students never work with students on projects or assignments. But it’s important to note that much of the collaborative work that goes on in universities is a result of capacity limitations: too many students and too little lab space. Dividing students into groups is often a pragmatic solution, not necessarily a pedagogical choice.

Questions Relating to Effective Teaching Practices

During the current academic year to what extent have lecturers…

1.Clearly explained course goals and requirements

2.Taught in an organised way

3.Used examples or illustrations to explain difficult points

4.Provided feedback on a draft or work in progress

5.Provided prompt and detailed feedback on tests or completed assignments

All reasonable questions but I’ll make one comment before showing the results: there is increased pressure on academics to provide students with rapid, personalized feedback, much of it coming from organisations like the National Forum for Teaching and Learning. Given that the role of academics is to do a lot more than teach, expectations around feedback especially around individualised feedback (and even more especially around feedback of drafts) and the rapidity of it need to be examined. It is quite easy for students to fall into a ‘satnav’ approach to receiving feedback.

Questions 4 and 5 above, which relate to feedback, show that for half of the student body the level of feedback is probably not what they would want. The solution in my view is to adopt a more whole-class, feedforward approach. People can only work so hard.

So what are my conclusions so far? So far I’m very disappointed. The questions are often vague and too discipline-specific. I’d like to see questions like

- How many hours of part-time work do you do each week?

- How long is your commute?

- What percentage of your lectures do you attend?

- For lab modules, how much time do you spend studying, in advance, the lab manual?

- Even though slides might be available on Moodle/Blackboard, do you take notes during lectures?

- During semester, how many hours per week do you spend on reviewing your notes

- How many hours do your per week do you spend on continuous assessment?

- Are your continuous assessments well spread out?

- How often do you glance at your phone during lectures?

- How often do you come to early morning lectures too tired to concentrate?

- Does your timetable encourage you to remain in campus all day?

- How happy are you with the study spaces in your institution?

Hopefully I’ll see some of these in Part II.